Guest Essay

TQM for Labs: A European point of view

Dr J.C. Libeer, Ph.D., Ph.D, joins us from Belgium, where he has put together a comprehensive survey of the European quality schemes and programmes, noting their strengths and weaknesses. A must for those who want to learn about and keep current with laboratory quality management in Europe.

Scientific Institution of Public Health - Louis Pasteur, Brussels, Belgium.

- Introduction

- Scope of medical laboratory analyses

- Internal and external quality control

- Total quality management in medical laboratories

- Introduction

- Table 1: Proposed guidelines for quality systems in medical laboratories

- Comparison of National Quality Systems

- Table 2: Evaluation of quality systems in medical laboratories according to Deming's quality elements

- Future development

- Is the quality system for the medical laboratory sufficient for assuring the medical output?

- References

- Biography: Dr. J.C. Libeer, Ph.D., Ph.D

Introduction

Westgard Web is pleased to provide this guest essay from Dr. Jean-Claude Libeer from Belgium. While Westgard Web tends to focus on quality systems for USA laboratories, we recognize there is a broader and more international interest in quality systems, as reflected by our web activity reports and the participants in our internet continuing education courses. Whereas USA laboratories are driven primarily by the national CLIA regulatory guidelines, European laboratories are developing quality systems that more closely follow international standards (particularly the ISO standards). In this essay, Dr. Libeer traces the development of European quality systems, identifies and compares their characteristics, and discusses their expected evolution, with particular attention to the ideas of medical competence and medical validity.

Scope of medical laboratory analyses

Medical laboratories are involved in medical trials and in patient care. In medical trials, laboratory tests performed in the pre-clinical phase must follow good laboratory practice (GLP) standards. Depending on the countries, several GLP standards are used. In the European Union, the GLP directive is based on the OECD guideline (1); the US GLP is controlled by the FDA. The general philosophy of GLP is based on concern about potential fraud and underscores the need for transparency of results and raw data. While the GLP has no particular standard for medical laboratories involved in test trials for pharmaceutical development during the clinical phase, guidance is found in Good Clinical Practice (GCP). These types of tests are generally linked to safety and efficacy studies. Recently, the pharmaceutical industry published recommendations on the interpretation of adequate laboratory facilities as outlined in GCP (2). Tests for patient care are mainly performed for (i) monitoring of drugs (TDM) or markers for the follow-up of a therapy or a health status of a patient and (ii) for diagnostic purpose as confirmation or as an aid for clinical diagnosis.

Internal and external quality control

Of all laboratory sectors, medical laboratories and especially clinical chemistry laboratories have a long tradition of internal and external quality control. In clinical chemistry laboratories, Levey and Jennings (3) introduced control charts as used in industrial processes and known as Shewhart plots or control charts (4). In 1981, Westgard published his first concept on the multi-rule Shewhart chart for internal quality control in clinical chemistry (5): the so-called "Westgard rules." He made benchmarking work on internal quality control in clinical chemistry and on total quality management (TQM) (6) in medical laboratories by using similar approaches from industry.

However, in some fields of laboratory medicine, internal quality control is even today not well developed (infectious serology, microbiology, parasitology) and will require an effort for improvement. During the last years we have also observed that in these fields internal quality control is more and more promoted and implemented. Recently, modern guidelines for internal quality control of analytical results in medical chemistry were published by Hyltoft Petersen et al. (7).

The first results of an external quality assessment survey were published by Belk and Sundermann in 1947 (8). Terminology for external quality evaluation programs are different in European countries and in the US. Proficiency testing (PT) as defined in CLIA is not the usual term in Europe. The term external quality control is now generally replaced by external quality assessment. Most of the programs are essentially educational and not limited to participant analytical performance evaluation. Therefore Olafsdottir even used a new term: external quality assurance (9).

External quality assessment (EQA) programs were introduced in many European countries, either by the Health Authorities, or by professional organizations. The ultimate objective of EQA is improvement of health care through improvement of laboratory performance. It is also supposed that EQA results reflect routine performance of the laboratories. However, this is not always true.

The difference between EQA and PT is not always clear; PT is rather used in the scope of laboratory accreditation conditioning based on results obtained in external schemes. In some countries, such as Belgium, Luxembourg, France and in several Eastern European countries, participation to the EQA schemes is mandatory, but there is no direct consequence of failing on the laboratory license. The regulation of medical laboratories by the Health Authorities was intended for several reasons: (i): to regulate public expenditure on health care; (ii): to prevent poor performing laboratories from practicing and (iii): to provide education, training and help.

A comprehensive thesis on external quality assessment was published by Libeer in 1993 (10). In the course of the years we have observed an evolution from quality control to quality assurance with more problem-related EQA concepts and a large educational role. This approach is described by Libeer et al. (11). Contacts between European EQAS organizations resulted in a first worldwide symposium during the IFCC congress in London in July 1996 and in the foundation of EQALM (European committee for External Quality Assessment Programmes in Laboratory Medicine) in the same year.

ISO/IEC guide 43 (12) gives recommendations for the development and operation of proficiency testing schemes. It is recommended that a quality system should be established and maintained within an EQAS organization. The WELAC ELA-G6 document (13) strongly recommends that the organizer should meet the requirements of quality assurance based on the appropriate parts of series EN 29000, EN 45000 or ISO/IEC Guide 25 demonstrated by accreditation or equivalent means. The European group of EQAS organizations has published minimum requirements (14) with a mandatory quality system for EQAS organizations for at least obtained in 1999. The Finnish EQAS organization LABQUALITY is preparing an ISO 9002 (15) certification. UK NEQAS will follow a quality system proposed by CPA (16) and the Belgian and Swiss EQAS organization are preparing a EN 45004 (17) accreditation.

Total quality management in medical laboratories

Introduction

Quality concepts in analytical laboratories are changing very quickly. In many fields of laboratory tests, accreditation has become a must. Within the European Union (EU), the EN 45001 (18) standard is recommended for all types of test laboratories. This standard not only requires technical competence and analytical quality management, but also the management of other quality aspects (human resources, structure of the organization, management of documents, etc.). The European EN 45001 standard is equivalent to the worldwide accepted ISO guide 25. For the moment ISO 25 is under revision and according to the ISO-CEN mutual agreement the new ISO 25 guide will replace the present EN 45001.

From a social point of view it would be unacceptable if other laboratories (e.g. analyzing foods and pet foods) were held to more stringent quality criteria than laboratories analyzing medical samples from patients. Therefore the medical laboratory profession had followed this evolution in many countries, but found the EN 45001 standard insufficient for covering all aspects of good medical laboratory services for the following reasons:

- In the medical laboratory, it is not sufficient to have only technical competence. Appropriate medical competence is also required.

- The medical laboratory may receive infectious patients and infectious samples and it performs tests using radioactive material or other dangerous substances. Due considerations shall therefore be given to safety aspects as regards other patients, personnel, other persons, and the environment.

- A request in a medical laboratory can be formulated by the requesting physician as an enumeration of tests or as an investigation of a well defined syndrome.

- Correct sampling includes also patient preparation.

- Subcontracting under the responsibility of the primary laboratory is usual in medical laboratories.

- Validation of results are taken to comprise not only analytical, but also biological, validity and diagnostic and therapeutic usefulness.

- Some general requirements for reports are not relevant to reports from medical laboratories.

- No interpretation of results is allowed.

For these reasons, many countries have developed specific proposals for quality systems for medical laboratories. A review is given in table 1.

| Table 1: Proposed guidelines for quality systems for medical laboratories | |

| Austria | Gute Analysen- und Laborpraxis (GALP) (19) |

| Belgium | Directive pratique pour la mise en place d'un système qualité dans les laboratoires agréés dans le cadre de l'INAMI (20) |

| Croatia | Model of quality manual (21) |

| Germany | Accreditation of medical/medical diagnostical laboratories (EURACHEM/D - ZLG - AML) (22) |

| France | Guide de bonne exécution des analyses de biologie clinique (GBEA) (23) |

| Scandinavian countries | Nordkem project for a model of quality manual for medical laboratories (24) |

| Spain | Model of quality manual (25) |

| Switzerland | Critères de fonctionnement des laboratoires d'analyses médicales (CFLAM) (26) |

| The Netherlands | CCKL guide of practice (27) |

| United Kingdom | CPA manual for laboratory accreditation (28) |

All these proposals try to cover either the pre-analytical phase (sampling, patient preparation, sample transport, etc.) and the post-analytical phase (biological and clinical validation of results) and include also national requirements that are not always relevant for a quality system.

Comparison of National Quality Systems

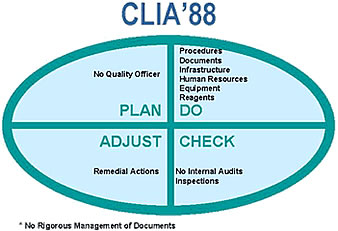

For the critical analysis of the proposed national quality systems, we used the PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Adjust) approach as developed by Deming (29). Applying this model to the CLIA requirements leads to the assessment in the accompanying figure. As observed in many European approaches, CLIA does not require a quality manual and a quality officer. Only technical procedures must be managed and the internal audit is not considered as an essential quality system management tool. Table 2 gives the essential requirements in each part and the implementation in several quality systems from different European countries. Major shortcomings are the lack of a quality manual (GBEA and CPA) and the completely forgotten internal audit and management review (CFAM, GBEA). With exception of the Austrian proposal based on ISO 9002, all others are based on relevant parts of ISO 9002 and EN 45001 or ISO 25. An external audit can be performed by peers or by an independent team, including also other persons. In the CPA and CCKL system some of the team members are medical technicians. Most of the proposals only accept an external audit by peers. In many countries, the mentality to accept the presence of other persons in the audit team, even medical technicians, is not present at the moment.

| Table 2: Evaluation of some quality systems for medical laboratories according to the quality elements from Deming. | ||||||

| Quality system elements | Belgium | GBEA | Nordkem | CFLAM | CCKL | CPA |

| PLAN | ||||||

| Quality officer | ||||||

| Quality manual | ||||||

| DO | ||||||

| Standard operating procedures (SOP's) |

||||||

| Management of documents | ||||||

| Infrastructural requirements | ||||||

| Human resources requirements | ||||||

| Equipment requirements | ||||||

| Reagents & standards requirements | ||||||

| CHECK | ||||||

| Internal audit | ||||||

| External audit | ||||||

| ADJUST | ||||||

| Remedial actions | ||||||

| 1: inspections by health authorities 2: assessment by an accreditation body 3: assessment by a professional (accreditation) body |

||||||

In the meantime, international organizations have tried to propose some more harmonized guidelines. ECLM (European Confederation of Laboratory Medicine) is in favor of accreditation rather than of certification of medical laboratories. Medical laboratories must follow at least appropriate standards and guidelines developed for laboratories. ECLM has reviewed the ISO/IEC Guide 25 from the point of view of medical laboratories in an explanatory document (30).

The EC4 group (European Community Confederation of Clinical Chemistry) produced a consensus document with essential criteria for quality systems in clinical biochemistry laboratories in the EU (31). Within ISO, the ISO technical committee ISO/TC 212, WG1 deals with quality management aspects in the medical laboratory and produced a committee draft document for a stand-alone quality management guideline for medical laboratories, based on ISO 25 (32).

Future development

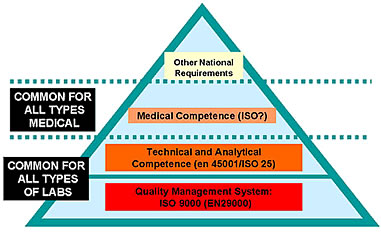

It comes as no surprise that all these different approaches embarrass the medical laboratory workers who are not specialized in this matter. The medical laboratory profession has often tried to demonstrate the unique features of their profession in regard to other laboratory fields and even to other countries. However, the same can also be demonstrated for every laboratory field. If we look more at the common elements than at the differences, it is possible to work out a harmonized approach on quality systems in accordance with other laboratory fields. Each national and even the international proposals for a quality system in medical laboratories can be split up in four levels as presented in the accompanying figure.

Medical laboratories can use the same approaches as other laboratory fields for their quality management system, and for their technical and analytical competence. In particular, the new ISO 25 guide covers all quality system elements from the ISO 9000 series and covers also many aspects of medical laboratories which had been criticized. With the exception of medical competence for the staff members and of more security aspects, the new ISO 25 covers also the requirements from the EC4 document. In order to maintain a harmonized approach, these complementary aspects could be combined in a third level. As social security systems, even within in the EU, are not yet harmonized, we will find some specific national (or regional) requirements in a fourth level. The new ISO/CD 15189 is a universal guideline covering the three basic levels for quality management of medical laboratories all over the world.

Is the quality system from the medical laboratory sufficient for assuring the medical output?

According to ISO 8402 (33), quality is defined as the totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs. Medical laboratories must provide a high quality service by producing accurate, precise, relevant and comprehensive data that can be applied to the medical management of patients. The tests requested must be appropriate to the medical problem, must be analytically correctly performed and their results interpreted correctly. Appropriateness of tests can only be obtained by a dialogue between the clinician and the medical pathologist. Correct analytical results are based on (i) quality management within the laboratory (ii) the quality of industrially prepared reagents (kits) and systems and on (iii) quality management of the pre-analytical phase outside the laboratory. A bad system, a wrong sampling or a kit with poor performance can never produce a reliable result, even in a laboratory with the best quality management system.

Medical diagnostic manufacturers and distributors are already convinced that a quality management system can improve the quality of their products and services. Most companies have already or are preparing a certification based on ISO 9001 or 9002 (34, 14) (In the EU, these guides are called EN 29001 and EN 29002; for medical devices the additional standards EN 46001 and EN 46002 (35, 36) are used).

For better protection of the patient, a European directive on in vitro diagnostic medical devices is in preparation (37). This directive imposes severe requirements on the manufacturers. The ultimate goal for better patient protection can only be guaranteed if more stringent quality criteria are also applied by the users of these kits, in casu the medical laboratories.

The new approaches will also require a new mentality in medical laboratories. The laboratory director and medical pathologists will be forced to review their management style. Delegation of responsibilities, motivation and persuasiveness will become more and more important. Laboratory workers will be forced to change habits and to take more responsibilities. The whole laboratory must be considered as one team, working together for the same goals: improved quality of results and demonstration of this quality to society. In order to maintain a high analytical quality level, periodic review of the quality system will be essential. This review must be done within the laboratory (internal audit and management review) and by an external party (external audit).

However, management of medical outcomes is not finished with the production of a correct analytical result. The analytical validation must be followed by a medical validation. Büttner (38) distinguishes two levels of clinical validation levels: (i) the biological level, where an individual result is compared to results obtained within a reference group (for screening situations) or with formerly obtained results from the same patient (for monitoring situations). (ii) the nosological level, where interpretations are based on an appreciation of all tests performed for the same patient at the same moment. The current ISO 25 guide and EN 45001 standard do not allow any interpretation of results and consequently they were considered worthless for medical laboratories.

The new ISO 25 guide is more appropriate and allows a professional judgment by personnel having applicable and practical background. This requirement is perhaps the most difficult to assess, because it is situated between the assessment of the laboratory as an organization and the assessment of personal intellectual capabilities of the staff members.

Nevertheless, clinical evaluation is essential and requires fundamental and practical analytical and medical knowledge. This knowledge is not always available in some laboratories. As an illustration, we mention here TDM. New technology allows every laboratory to measure drug levels. A quality system can guarantee a correct analytical result. However, the interpretation of these results requires fundamental and practical knowledge of pharmacokinetics, therapeutical range and metabolism. Results without medical validation are worthless for the clinician; yet currently many mistakes are observed in the information given to clinicians because of a lack of knowledge by laboratory staff.

The very rapidly changing techniques and the introduction of new tests will require a continuous training of laboratory workers. Although continuous training is a must in each profession, a mandatory system has been installed in several countries for medical staff. In these systems a number of CFU (continuous formation units) must be collected during a year. However this system does not guarantee that medical laboratory staff has real competence for all those analytes performed in their laboratory. This knowledge concerns not only new technology, such as DNA amplification techniques, but also new applications of well-known technology.

Management of medical outcome in medical laboratories is a challenge for the future and must be based on two essential requirements: the implementation of a quality system in medical laboratory organizations and a reconsideration of the tasks of medical pathologists.

References

- OECD. Committee for the final report of the working group on mutual recognition of compliance with good laboratory practice. ENV/CHEM/CM 87.7. OECD Environment Monographs 1988 (no.18): 25-35 & 41-54, Paris.

- The Medical Laboratory's Role in GCP Compliance. EFGCP Audit Working Party. Applied Medical Trials: 42-47, 1996.

- Levey S. and Jennings ER. The use of control charts in the medical laboratory. Am. J. Clin. Pathol.20:1059-66, 1950.

- Shewhart WA. Economic control of quality of the manufactured product. Van Nostrand, New York, NY, 1931.

- Westgard JO., Barry PL., Hunt MR and Groth T. A multi-rule Shewhart chart for quality control in medical chemistry. Clin. Chem. 27: 493-501, 1981.

- Westgard JO. and Barry PL. Cost-effective quality control: managing the quality and productivity of analytical processes. AACC Press, 1725 K Street NW, Washington DC-20006, 1986.

- Hyltoft Petersen P., Ricos C., Stöckl D., Libeer JC., Baadenhuijsen H., Fraser CG., and Thienpont L. Proposed guidelines for the internal quality control of analytical results in the medical laborarory. Eur. J. Clin. Clin. Biochem. 34(12):983-999, 1996.

- Belk W. P. and Sunderman F. W., A survey of the accuracy of chemical analyses in medical laboratories. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 17: 853-861, 1947.

- Olafsdottir E, Hellsing K, Steensland H, Terhunen R, Uldall A. Adding new scopes to traditional EQA schemes emphasizing quality improvement. In: Hyltoft Petersen P, Blaabjerg O, Irjala K, editors. Assessing quality in measurements of plasma proteins. The Nordic Protein Project and Related Projects. Nordkem Medical Chemistry Project, Helsinki, Finland, 1994:187-94

- Libeer JC. External quality assessment in medical laboratories. European perspectives: today and tomorrow. University of Antwerp 1993.

- Libeer JC., Baadenhuijsen H., Fraser CG., Hyltoft Petersen P., Ricos C., Stöckl D., and Thienpont L. Characterization and classification of external quality assessment schemes (EQA) according to objectives such as evaluation of method and participant bias and standard deviation. Eur. J. Clin. Clin. Biochem. 34(8):665-678, 1996.

- ISO/CASCO 322: ISO/IEC guide 43-1: Profciency testing by interlaboratory comparisons -Part 1: Development and operation of proficiency testing schemes. Voting draft 1996.

- European Laboratory Accreditation Publication. WELAC Guidance Document WGD4 ELA-G6, 1993.

- Bullock DG., Libeer JC. and Zender R. Minimum requirements for external quality assessment schemes for medical laboratories in Europe. EQAnews, 5(2): 1-2, 1994.

- ISO 9002: Quality systems - Model for quality assurance in production, installation and servicing. Geneva ISO 1994.

- CPA draft standard for the accreditation of EQA schemes, 1995

- European standard EN 45004: General criteria for the operation of various types of bodies performing inspection. CEN/CENELEC 1995. The joint European Standards Institutions.

- European standard EN 45001, CEN/CENELEC. 1989. The joint European Standards Institutions.

- Österreichische Gesellschaft für gute Analysen- und Laborpraxis (GALP), 1995.

- Commission of Medical Biology: Practical guideline for clnical laboratories 1996. IPH, Brussels.

- Hammer-Plecas A., Cvoriscec D., Stavljenic-Rukavina A. Guideline on quality manual design, with paricular reference to internal quality control within a medical biochemistry laboratory. EQAnews 6(3): 49-51, 1995.

- Guideline for the implementation of the EN 45001 and ISO Guide 25 Standards. Eurachem, sector committee "Medical Laboratories" of the Centre for the Federal States for Health Safety in Medicinal Products (ZLG), Working Committee "Medical Laboratory Diagnosis" (AML).

- Guide de bonne exécution des analyses de biologie médicale (GBEA). Arrêté du 2 novembre 1994 relatif à la bonne bonne exécution des analyses de biologie médicale Journal Officiel de la République Française, 17193-201, 1994.

- Dybkær R., Jordal R. , Jørgensen P. J., Hansson P., Hjelm M.,Kaihola H.-L., Kallner A., Rustad P., Uldall A. and De Verdier C.-H. A quality manual for the medical laboratory including the elements of a quality system. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 53 (suppl. 212): 60-84, 1993.

- Recommendaciones para la acreditaciÓn de laboratorios clinicos (volumen 1) ed. Bauza, SEQC, 1996.

- Critères de fonctionnement des laboratoires d'analyses médicales (CFLAM), Union Suisse de Médecine de Laboratoire. Draft 1.11, 1994.

- CCKL (Laboratory Care in the Netherlands) Loeber J. G. en Slagter S., Code of practice for implementation of a quality system in laboratories in the health care sector. CCKL Bilthoven 1991.

- Accreditation Handbook. Medical Pathology Accreditation. Dr. Lilleyman J. S. CPA Project Office. The Children's Hospital Western Bank, Sheffield S10 2TH UK, 1991.

- Deming W.E. Out of the crisis. MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study, Cambridge, M.A. 1982.

- EAL/ECLM. Accreditation for medical laboratories. Guidance on the interpretation of ISO/IEC Guide 25, 1995.

- Jansen R.T.P., Blaton V., Burnett D., huisman W., Queralto J.M., Zérah S. and Allman B. Essential Criteria for Quality systems of Medical Laboratories. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 35:121-122, 1997.

- ISO/CD 15189. ISO TC 212 WG 1 document on quality management in the medical laboratory 1997.

- ISO 8402. Quality - vocabulary. Geneva ISO 1990

- ISO 9001. Quality systems - Model for quality assurance in design development, production, installation and servicing. Geneva: ISO. 1993.

- EN 46001: Quality systems - Medical devices - particular requirements for the application of EN 29001, 1993.

- EN 46002: Quality systems - Medical devices - particular requirements for the application of EN 29002, 1993.

- Proposal for a European Parliament and Council directive on in vitro diagnostic medical devices. European Commision, Brussels, April, 1995.

- Büttner J. Diagnostic validity as a theoretical concept and as a measurable quantity. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 33:A104-105, 1995.

Biography: Dr. Pharm J.C. Libeer, Ph.D. Ph.D.

Head of the Clinical Pathology Department

Scientific Institution of Public Health

Brussels, Belgium

Dr. Libeer graduated in pharmacy at the University of Ghent in 1973 and became a qualified clinical pathologist in 1985. He earned his Doctorate in toxicology (1979) and his PhD at the University of Antwerp (1993) with a thesis related to external quality assessment in clinical laboratories.

In 1979, he joined the Scientific Institution of Public Health and became involved in clinical laboratory licensing. Since 1988, he has coordinated the official Belgian external quality assessment programmes and headed the Clinical Pathology Department in the same institution.

Besides his normal tasks, he is actively involved in several European working groups concerning external quality assessment. He is chairman of EQALM, the European umbrella of EQA organisations. At the University of Antwerp and Louvain, he is involved as a lecturer in a postgraduate course on total quality management in clinical laboratories. His department is also active in research activities related to quality and commutability of control materials. Finally, he is GLP assessor and both technical and head assessor within BELTEST (Belgian accreditation body for test laboratories according to EN 45001).