ISO

Internal audits based on ISO 19011 good practices for medical laboratories fulfilling ISO 15189

In Part 5 of our series of ISO Updates, Dr. Paulo Pereira discusses how to conduct Internal audits based on ISO 19011 good practices for medical laboratories fulfilling ISO 15189 and ISO 9001 specifications

ISO SERIES UPDATE

Part 5 - Internal audits based on ISO 19011 good practices for medical laboratories fulfilling ISO 15189 and ISO 9001 specifications

Paulo Pereira, Ph.D.

May 2018

Introduction

Internal audits are commonly required in any quality management system. Their role is essential to the medical laboratory since they are closely related to continuous monitoring, nonconformity reports, and opportunities for improvement. They are required both by ISO 15189 [1] and ISO 9001 [2] (see ISO series update Part 1 - ISO 9001:2015 applied to medical laboratory scope and Part 2 - ISO 15189:2012 “Medical laboratories - Requirements for quality and competence”). Typically in the early stages of an accreditation or certification project, some misunderstandings about how to conduct an internal audit properly can occur. Let us consider the case where the auditor and the audit costumer have not fully understood the standards. In this scenario, there is a high risk of misinterpretation; nonconformities could be interpreted as conforming, while perfectly conforming processes could be interpreted as nonconformities. It should also be understood that most medical laboratory quality management systems are not exclusively ISO systems, but a combined system based on ISO specifications and local regulatory requirements. The purpose of this lesson is to support the laboratorian to perform reliable and consistent audits.

Approach

ISO 15189 and ISO 9001 standards share similar specifications for internal audits. Both suggest the use of ISO 19011 “Guidelines for auditing management systems” [3] for guidance. This standard is essentially a guide to the best practices of auditing. It “does not state requirements, but provides guidance on the management of an audit programme, on the planning and conducting of an audit of the management system, as well as on the competence and evaluation of an auditor and an audit team.” ISO 19011 can be applied to different models of audits (see Table 1). It is applicable also to vertical or horizontal audits. Vertical audits are those that follow the production process. Horizontal examinations are focused on a specific area or activity/activities of the process. Typically, the vertical model is chosen. For instance, the horizontal audit can be performed in areas with high risk of non-conformities. Its application to internal or external audits has critical differences. This lesson is oriented to internal audits on quality systems based on ISO 15189 and ISO 9001 principles.

| Audits Focused on the organization | Audits Focused on the operator | ||

| Internal Audit (first party audit) |

External Audit |

Individual Audits |

|

| Supplier audit (second party audit) |

Third party audit for legal and regulatory and similar purposes such as accreditation or certification |

||

| Table 1: Types of Audits | |||

Interpretation of quality management standards

The understanding of quality management standards is critical to the success of any audit. A successful plan, audit, and report are dependent on the correct interpretation of the guidelines. An adequate matrix of skills is mandatory for the auditors and, when applicable, technical experts. The audit team should be well versed in the principles of quality management and audit. Note that ISO 19011 refers audit team as “one or more auditors conducting an audit, supported if needed by technical experts” (3.9 of [3]). ISO considers that “shall” stipulates a requirement, “should” identifies a recommendation, “may” specifies permission, and “can” specifies a possibility or a capability. See the previous ISO Update lessons for the interpretation of standards specifications.

Principles of audit

ISO 19011 presents the following principles to assure the success of audit (4 of [3]):

a) “Integrity” is the basis of professionalism;

b) “Fair presentation,” is understood as the responsibility to report honestly and correctly;

c) “Due professional care” mandates diligent practice and consistent decisions in auditing

d) “Confidentiality” indicates the importance of maintaining the security of the audit report and its private review only by the auditees.

e) “Independence” guarantees the neutrality of the audit and impartiality of the audit conclusions, and;

f) “Evidence-based approach” assures that a rational method is applied to getting reliable and reproducible audit conclusions.

Good practices of an audit management system

Documented procedure

ISO 9001 does not require that the audit procedure must be documented. However, ISO 15189 requires its documentation (4.14.5 of [2]). Both standards require that the records related to needed audit activities must be retained/controlled. Even in medical laboratories with a quality management system certified according to ISO 9001, the procedure documentation is critical for the harmonization of the practice in the lab such as an essential tool for auditors in training. The documented minimum steps are what is required (=shall) on the standards. An extra on the document could be based on ISO 19011 guidance.

The profile of the auditor

The internal audit to be carried out, the med lab must use competent and independent personnel with experience in the activity being audited - to assure the auditor is objective and impartial. It can be done by defining the competencies needed to qualify the internal auditors and should take into account the knowledge of several areas, established on a case-by-case basis. For instance, taking into account the lab dimension, processes, and services. Let assume the theoretical knowledge, technical and professional expertise, social and relational skills, and cognitive abilities for a detailed profile. The persons carrying out the internal audits may be internal or external to the lab. The independence and impartiality of auditors can be demonstrated by the lack of responsibility and conflicts of interest with the area to be audited. Such as any other professional, the auditors should have specific formation and, when applicable, be evaluated (7.2 of [3]).

Management of the audits’ program

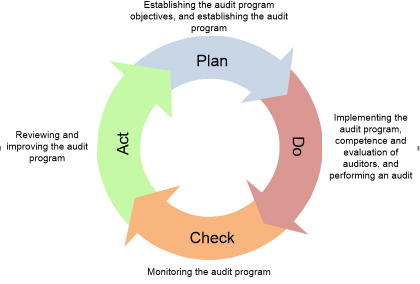

Both ISO standards require that the med lab conducts internal audits at scheduled intervals. ISO 15189 suggests (=should) that the audits can occur annually. Note that the audit to the quality management system, including the pre-examination, examination, and post-examination phases happen within the certification or accreditation three-years cycle. Therefore, it is not expected that the full management system is audited during this period. The program requires the frequency, techniques, responsibilities, planning specifications, and reporting. These requirements are based on the relevance of the processes, critical changes, and past audit outcomes. The program must take into account the condition and relevance of the processes such as of the technical and management fields on the audit. The audits’ program must conform to the ISO specifications and any other requirements established by the med lab. For instance, the previous internal audit cycle suggests that to audit all the management system with two auditors is a complex task, so, the program is reviewed accordingly. Or the case, where it is recognized that a particular area of the lab is susceptible to nonconformances. So, the audit to this field is primary when compared to the other lab areas. It is mandatory that the program is realized, actual, and maintained. The program should contribute to the determination of the effectiveness of the auditee’s management system (5 of [3]). Figure 1 displays a the quality-cycle to the management of the audits’ program. The primary goal of the cycle is the continuous improvement of the audit performance.

Figure 1. View of PDCA cycle applied to the management of audits' program based on ISO 19011 stages.

Audits’ planning

The audit planning should provide an agreement between the audit client, and the auditors. It should contemplate an adequated sampling technique; for instance, based on the sensitivity of the audited area to nonconformities or based on the control of a change. A Pareto-based thinking could be used to support the selection of the samples to be audited. The audit criteria should be defined. It is recognized as a group of policies, techniques or specifications used as a reference to which the evidence is compared (3.13.7 of [4]). The criteria must be clearly defined in each of the audit plans. For instance, which clauses of ISO are audited, and which laws are audited. The degree of detail should reflect the scope and complexity of the audit. The scope must also be precisely defined. Typically, the scope of an audit is equal to the scope of the certification or accreditation when the audit is to the entire management system, such as happens in a third-party audit. For instance, when just a field of the lab is audited the audit scope should be the associated part of the management system scope. The plan should also have the auditor(s) (and technical experts), a schedule, and any other information important to the good communication of the audit to the lab staff. Usually, the preparation of the audit is based on a review of documentation, including previous audits’ reports and records. Depending on the quality system, this review could even sometimes interpreted as an off-site audit. For instance, in the case where all records are stored in an electronic database, e.g., quality control, control of changes, and control of occurrences archives, audits could be performed on-site or remotely. They can be performed with or without face-to-face staff interaction. The on-site audit is performed in the space where most of the audited activities are performed. Remote audits are appropriate when most of the audited events are occurring outside of the location. It could be a successful alternative and a more sustainable audit program. ISO 19011 suggests (not mandatory) good practices for “Additional guidance for auditors for planning (…)” in supplements. For further details see (Annex B of [3]).

Establishment of audit teams

The number of auditors should equal the need to complete an audit in a thorough but timely fashion. Each audit team should have an auditor coordinator. The coordinator has the responsibility for communication with the client and to adjust and manage the auditing plan. The auditors should also be selected according to the skills related to the area to be audited. For instance, if one of the auditors has expertise in quality control, he should be the primary choice to check these technical specifications. When there is no auditor available with an adequate matrix of skills for a particular area, it is suggested to include the participation of a technical expert. When there is no one with expertise available in the audited area, there is a high risk that some evidence could be misunderstood (5.4.4 of [3]).

Conduct of the audit

The opening meeting should be a brief introduction from the auditor coordinator. This plan aims to synchronize auditors with their clients, clarify any doubts and possibly adjust the plan. For instance, in a one day audit, if there is an unusual change in the daily routine of the lab, the morning and afternoon audit schedule will be adjusted accordingly.

During the audit, several good practices should be followed. The audit evidence collected is based on a representative sample. The audit coordinator or audit team should assure periodic communication with the client. The auditor coordinator should inform the client about the progress of the audit. If the auditors detect any critical nonconformity needing an immediate correction, it should be immediately communicated to the client.

During the audit, the collection and verification of information should be evidence-based. If the related occurrences are not factual, they can not be sustained, which makes the reports fragile and makes the actions to be taken by the client a complex challenge. For instance, if an auditor identifies a particular document as nonconforming, but if he merely reports that “documents are nonconforming to ISO specifications,” the audit client may justifiably ask if the reported nonconformity applies to one or all the documents and, within the document, which specifications are nonconforming. This bad practice does not help the lab to improve the quality system, making a simple improvement a complex challenge. Writing an evidence-based is usually the first challenge for a beginning auditor. The audit team should collect evidence of the lab staff audited. For instance, using a signed and dated list of the participants.

The auditor coordinator leads the final meeting. He should present a brief audit conclusion, considering the objectives and the findings that not only lead to the identification of non-conformities, but also to the description of opportunities for improvement or recognizing the good practices. According to auditors’ expertise, an action plan to treat the occurrences could be discussed. This plan is oriented to successful corrections, and corrective actions/preventive actions (CAPA) (6.4 of [3]).

Preparation of the audit report

The audit report could be finished and presented during the audit or after. Typically, it is immediately accessible in third-party audits, and it is presented after the audit in internal audits. When it is not available in internal audits, it contains what was presented at the closing meeting. If there are any significant differences, it could contribute to misunderstandings by the auditee. The report could have as annexes a sheet with the name, signature and identification code of the auditees, such as any relevant evidence.

The report should include the audit client, audit objectives and scope, a comment on the degree to which the audit criteria have been satisfied, the audit team and auditee’s personnel that participate in the audit, be traceable to the time and dates, be attributable to the areas where it happened, the audit criteria, the audit findings and related evidence by type of finding (non-conformity, opportunity of improvement), and the audit conclusions (6.5 of [3]).

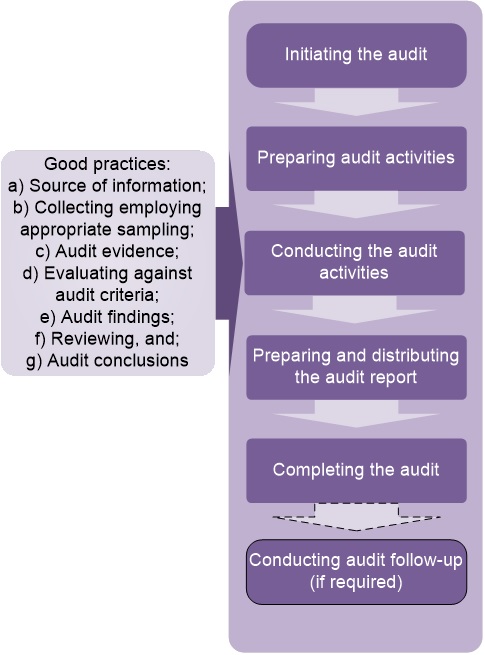

Figure 2. Flowchart of the audit process

Audit follow-up

The medical laboratory should have a timeframe for corrective actions and actions for opportunities for improvement (preventive actions) to mitigate risk. This timeframe could be based on risk assessment of the findings. Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) could be applied to risk-based thinking (0.3.3 of [2]) decision. Depending on the laboratory policy of quality, the audit team could follow the implementation of actions. In some cases, the follow-up could occur in the next audit where the same or a different audit team verifies the success of actions. On the follow-up, the audit team could give consulting, depend on the matrix of skills of the auditors (6.7 of [3]).

Figure 2 summarizes the sequence of the stages of the audit process.

Summary

The pros could be summed up as:

- Internal audits are recognized as a good practice to control the specifications of a quality system independently

- ISO 19011 is intended for any quality system

Nevertheless, there are a few cons:

- The success of audits depends on the matrix of skills of the auditors

- The findings are based on a sampling

References

- International Organization for Standardization (2012). ISO 15189 Medical laboratories - Requirements for quality and competence. 3rd ed. Geneva: The Organization.

- International Organization for Standardization (2015). ISO 9001 Quality management systems - Requirements. 5th ed. Geneva: The Organization.

- International Organization for Standardization (2011). ISO 19011 Guidelines for auditing management systems. 2nd ed. Geneva: The Organization.

- International Organization for Standardization (2015). ISO 9000 Quality management systems - Fundamentals and vocabulary. 4th ed. Geneva: The Organization.